In 1945, as all combatant nations were recovering from World War II, a notable “friendly” football (soccer) match took place in England. Football had been put on ice since 1939, and fans and athletes alike were eager for a resumption of the action. A Russian armed forces team had scored impressive victories over both its British and French counterparts, and the time had come for a top Russian team to take on a top British club. And thus it was that on November 13, 1945, FC Dynamo Moscow arrived at Stamford Bridge to take on Chelsea FC. The attendance was officially listed at 74,496, but the true attendance is usually estimated to be between 100,000 and 120,000. Chelsea led at halftime 2-0, but the Dynamos were able to make it 2-2, and each side tacked on another goal each before the end of play. (Four days later, the Dyamos walloped Cardiff City 10-1.)

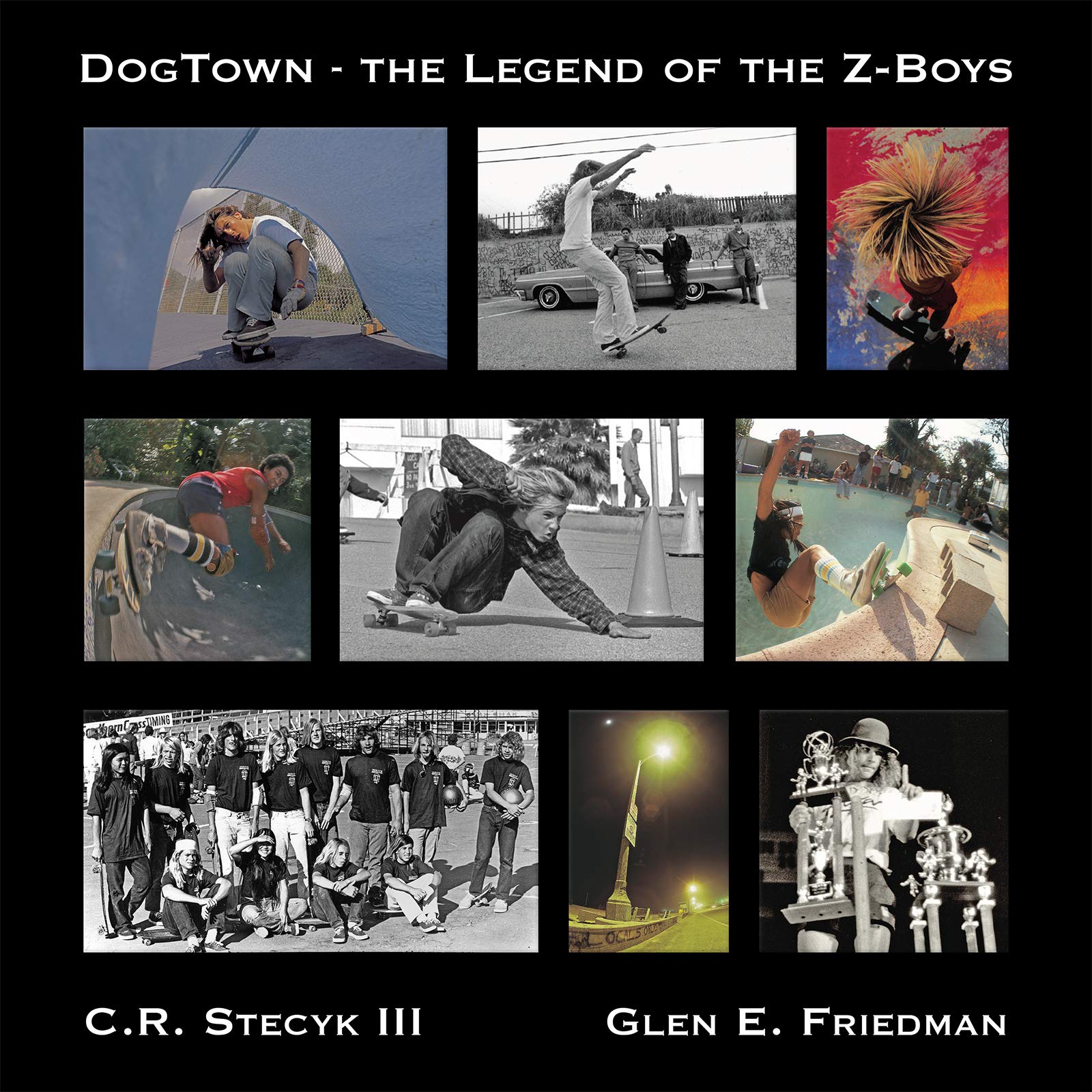

A Chelsea shot narrowly misses against the Dynamos.

About a month after FC Dynamo Moscow went home, a prominent (but hardly famous) journalist for the Tribune named George Orwell published an acid reflection on the nature of nationalism and athletics. In the piece, titled “The Sporting Spirit,” Orwell argued that, contrary to all assurances that nation-based sports competitions foster brotherhood and understanding among the peoples of the world (you will hear endless statements from Sochi over the next two weeks), such events, if anything, generate a modicum of ill will among national groups. The whole thing, according to Orwell, has the flavor of the jingoism that is whipped up before all wars.

Orwell clearly had little interest in sports and is missing part of the picture of fandom for a national team (or even a regional team like our pro squads), but the part he gleaned is instructive, and the entire essay is worth reading. Here are some of the choice bits:

Now that the brief visit of the Dynamo football team has come to an end, it is possible to say publicly what many thinking people were saying privately before the Dynamos ever arrived. That is, that sport is an unfailing cause of ill-will, and that if such a visit as this had any effect at all on Anglo-Soviet relations, it could only be to make them slightly worse than before….

As soon as strong feelings of rivalry are aroused, the notion of playing the game according to the rules always vanishes. People want to see one side on top and the other side humiliated, and they forget that victory gained through cheating or through the intervention of the crowd is meaningless. Even when the spectators don’t intervene physically they try to influence the game by cheering their own side and “rattling” opposing players with boos and insults. Serious sport has nothing to do with fair play. It is bound up with hatred, jealousy, boastfulness, disregard of all rules and sadistic pleasure in witnessing violence: in other words it is war minus the shooting….

If you wanted to add to the vast fund of ill-will existing in the world at this moment, you could hardly do it better than by a series of football matches between Jews and Arabs, Germans and Czechs, Indians and British, Russians and Poles, and Italians and Jugoslavs, each match to be watched by a mixed audience of 100,000 spectators.

Orwell’s bleak conception of sports wouldn’t change over the years. A few years later, in his novel 1984, the following sentence appears: “Heavy physical work, the care of home and children, petty quarrels with neighbors, films, football, beer and above all, gambling filled up the horizon of their minds. To keep them in control was not difficult.”

Here’s a brief Russian report on the Dynamos-Chelsea match. Note the throngs of spectators crowding along the sidelines.

Thursday, February 13, 2014

George Orwell’s special Olympics message: Sports are bunk

another from Dangerous Minds

Labels:

george orwell,

nationalism,

olympics,

sports

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment